Baiting Owls

Cover photo by Justin Cale

A Note to Readers: The purpose of this article is to educate, bringing together diverse resources and information about baiting owls. The Birding Project has a diverse audience of amateur to expert bird admirers, researchers, authors, students, birding guides, photographers, and professional ornithologists. Learning is a key piece to conservation. The more we know, the more we understand how nature works, and the better job we can do at preserving it. This post aims to educate and inspire. If you enjoy this, please help the message reach more people by sharing this post with others.

Photo by Justin Cale, of an un-baited Great Grey Owl. Many times these owls can be observed hunting wild rodents if the photographer has the patience and speed to keep up.

For thousands of years owls have drawn human attention from cultures around the world. Ancient people revered and respected owls, and in some cultures they are intertwined with superstition and mythology. For many birders, spotting certain owls is almost mythical, as they are routinely some of the most hard to find and sought-after birds in North America. Every winter, birders travel to airports, cornfields, and bogs in hopes of spotting one of many northern visitors, pushed southbound by natural miracle of migration. There is usually a steady influx of northern owls annually, yet some years consist of larger south-bound movements, referred to as "irruptions".

Even in present day owls continue to elicit mixed feelings and spark controversy, specifically around the topic of baiting. Chances are, you've seen a photo of a baited owl, or watched on TV in amazement as an owl swoops in over the snow and appears to pounce next to the camera in an epic shot. These images and video footage often leave us speechless and so in awe that we often forget to question the legitimacy of the shot. Why should that matter? Well, many photographers justify their images as a way to educate people and as a conservation tool. However, as the first link above shows, there's nothing natural about owls catching mice on top of the snow- rodents will tunnel underneath the snow, where food is located and safety is key. In the second link, multiple shots of multiple owls are used, edited together to tell a story- however important details are overlooked, like the loud "swooshing" sounds accompanying the owl's otherwise-silent wingbeats edited in for the stimulation of a generation that needs sounds in every shot. There's no doubt in my mind that baiting was employed to get the footage in this clip.

For those unfamiliar with the term, baiting is the act of using a lure or attractant to bring an owl closer to the viewer. In this practice, live mice are frequently tossed out onto the snow in order to lure the owl in closer- resulting in an easy meal for the owl, and close looks / action shots for the viewers. Sometimes people use mouse-shaped cat toys attached to a string as a lure. Another type of baiting is audio baiting, or using playback or sound recordings to draw the owl closer into view. Many winter "owl prowls" use playback to attract or lure unseen owls from deep in the woods closer to the group, to provide a glimpse for participants to see an owl. The line gets blurry around audio luring, as many birders use this technique to find and spot birds, but current opinions from acoustic researchers believe it alters bird's natural behaviors and increases energy output to investigate and defend against "audio" intruders.

In an age of instant bird reporting, and social media acting as a conduit for sharing bird photos, more and more people are heading out in search of owls, armed with cameras. A single bird at a rural location can be publicized and photos celebrated,

Multiple award-winning wildlife photographers frown on baiting owls, and many organizations and photo contests, like Audubon Magazine- prohibit baited owl photos.

Why is baiting owls bad?

In June of 2016, I spent time with owl researcher and Project SNOWstorm co-founder Scott Weidensaul, who wrote this piece on the ethics of owl baiting. Scott emphasizes two main reasons why baiting owls shouldn't happen:

Owls don't need the food, and it puts them at risk.

Many people have good intentions putting mice out for owls, thinking that they are starving, but that is seldom the case. Research shows that during irruption years, Snowy Owls move further south as a result of a productive breeding season, creating a "bumper crop" of young owls. These owls, when caught to be fitted with transmitters are often plump and healthy overall. Providing food for these owls can pass along diseases from captive rodents to birds that may already be vulnerable to disease, as well as habituate them to being fed by people. More importantly, baiting owls is frequently done near roads, increasing the already high chance of vehicle collision resulting in the death of the owl.

Baiting Owls Changes Their Behavior

In Audubon Magazine's Guide to Ethical Bird Photography, it is written "Luring birds closer for photography is often possible but should be done in a responsible way" -- quickly followed by "Never lure hawks or owls with live bait, or with decoys such as artificial or dead mice. Baiting can change the behavior of these predatory birds in ways that are harmful for them"

If you're unsure if baiting changes the behavior of owls, watch this video. It's pretty convincing.

Stills from the video of a taunted owl.

The camo isn't working, it's just a hungry owl.

Northern Hawk-Owl Photo: Laura Keene

Northern Hawk-Owls are nomadic, and regularly disperse outside of their northern breeding range. This is part of the natural history of this species, following cyclical fluctuations of voles, their primary prey. I've heard accounts of Hawk-Owls near roadways leaving their perches and flying in to investigate when they hear a car door close, as a result of being fed by visitors. These owls that become habituated to hunting near roadways are flying low in pursuit of prey (baited or otherwise) and can easily be struck by a car. I read in a Canadian blog about that happening several times.

A Great Gray Owl perched on a photographer's lens in Canada. Photo: The Afternoon Birder

One doesn't need to look far to find stories of owl baiting. I found this blog post from The Afternoon Birder, a Canadian bird blogger who found herself several weeks ago in the middle of a group of people baiting a Great Gray Owl in Ontario, Canada. I'd encourage you to read her experience, view her photos, and think about what you would have done in this situation. She was moved to write about and share her experience, as well as start a hashtag #ethicalowlphoto for pictures taken free from influence of bait.

Is every owl shot baited? No! Sometimes a photographer is just in the right place at the right time. Patience, persistence, and a knowledge of the bird's behavior and biology can do a lot for a good photographer.

This Snowy Owl is oblivious to photographer Kevin Knutsen's presence nearby in his car blind. One can observe unique behaviors at a respectful distance, if the owl obliges.

Laura Erickson's excellent blog post on this subject of baiting owls highlights some issues around baiting owls, including how it cannot be accurately compared to backyard bird feeding. Her post pulls together some valuable resources I won't intentionally duplicate here.

In Canada, birders and photographers face the same issues we do, just with slight variances in the law. This news story highlights the negative impacts of baiting owls in Ottowa.

Boreal Owl photographed by Laura Keene, 2016 Big Year birder and role model to many female birders!

As a amateur photographer, I admire the work of professionals, buying their books and hoping someday to make images as unique and inspirational as their work. Sometimes good photographers make poor decisions. Nobody is perfect, yet it takes consistently practicing what you preach if you want the respect and accolades you work so hard to have your images reflect. I've lost some respect for several photographers who have pushed the boundaries of ethically photographing owls.

Where is the line?

In February 2013, up to 7 Boreal Owls were reported in the same area along a rural road in French River, Minnesota. Dozens of birders made the trek out to see what for many of them was their "lifer" Boreal Owl, a species normally found in secluded spruce forests. The owl was easily seen from the road, hunting voles 15 feet from the shoulder in front of a sizable crowd of over 30 people. The owl would wait for voles to tunnel out of the shoulder and run frantically across the road to the other side. The opportunistic Boreal Owl would drop down from the tree line, and easily capture the voles, then fly into the forest to cache the voles to eat later.

One professional photographer who had traveled thousands of miles to be in this location and photograph Boreal Owls for his book, went into the woods after the owl's successful hunt, intent to capture photos of the bird "caching" or storing the meal. As he left the roadway and went into the trees, people shouted in protest, upset that he broke from the masses to pursue the owl into the forest. His behavior likely didn't bridge any ethical line in regards to the owl which eventually returned later in the day, but it certainly negatively affected the people who had assembled along the roadway to watch the owl and all followed the group rules.

Birding for most of us is about enjoying the birds. However it is also about the people. This second part is what many folks forget when they are in the midst of the euphoria of seeing a new bird, or are intent on getting "the shot" -- professionals included. But there's this truth: People are watching you. New birders, impressionable young birders, and people who are not birders. (Land owners, news crews, and the general public passerby) As an observer, your actions affect the group as a whole as demonstrated by the previous story. Dozens of people left the scene angry, upset, and flustered, because of the selfish actions of one guy. Did I buy that photographer's latest book on Owls? Nope.

Professional photographers and cinematographers should be held accountable by the same standards as everyone else. They may know more about the behavior of the birds because they spend thousands of hours pursuing and studying their subjects. However, this does not excuse poor decision making around other people, or cutting corners just to get "the shot" and the next paycheck. Recently a video has been circulating Facebook, highlighting an encounter between two photographers, one baiting a Great Gray Owl hunting next to a road. (You can find said video on The Birding Project's page) This filmmaker, whose footage has appeared on National Geographic and other well-known sites certainly knows better than to take shortcuts that affect not just the bird but the people who came out to watch the bird. When confronted they said, "we did check with a bunch of people ahead of time, who said if that was necessary than it was ok..." I don't know who they checked with, but some producer at National Geographic shouldn't be calling the shots in this case, that's for sure.

The Response

Is there a solution to stopping the baiting of owls?

As The Afternoon Birder experienced, birders can be unexpectedly caught in the midst of a baiting scenario. This can be uncomfortable, especially in a group setting where the actions of one person affect everyone else. Everyone deserves the opportunity to see an owl in the wild, behaving like a wild bird should. It only takes one person to ruin the experience of the whole group. If we unite together, and oppose the baiting of owls, we can bring change. Every winter this discussion breaks out in multiple states, in the news, and on birding forums. It's time we learn a little, and then help change occur. The Birding Project encourages you to engage, but not enrage.

How Can I Help?

Many people want to know how they can be part of the solution. My advice is to get involved! When you see someone doing something that isn't right... PAUSE. Taking a minute before you react often is helpful in making sure that you don't contribute to the problem. Then, engage them in a respectful way. Sometimes people don't know what they're doing is wrong. Other times, they do know better. Although baiting isn't an illegal practice in many states, it is criticized by major birding, conservation, and photography organizations.

-Make your voices heard online, too. Hold people accountable for taking ethical photographs of wildlife. Be respectful. As I understand it, Minnesota has been trying to pass laws to prohibit owl baiting. As far as I know, that isn't in effect, and won't be until they hear from you.

-Contact Audubon, National Geographic, and other outlets for owl photos and footage, encouraging them to refuse images and video of baited owls. Right now there's a video circulating on Facebook of a film company who recently baited a Great Gray Owl while filming "for National Geographic". Let them know we don't want to see footage of baited owls because a cameraman couldn't wait to get the shot or "asked permission" from other people.

-Refrain from posting exact locations of wintering owls. Websites like Project SNOWstorm delay real-time reporting of the location of their owls, to reduce the likelihood of photographers finding and baiting the birds, which has happened in the past. You can use general locations on eBird to report your sightings- instead of noting exactly where the bird is, opt for a county instead.

-Use the hashtag #ethicalowlphoto to support the growing community of photographers who are taking an ethical stand to share their owl photos obtained ethically and without bait. Join the group of birders who are standing up for not only owls, but for other birders too.

Remember the first time you saw an owl? Let's help someone else experience that amazement and wonder too. Hopefully it will be the first of many spectacular encounters with nature.

Resources:

Project SNOWstorm: A great blog about Snowy Owl movements across the Northern U.S. http://www.projectsnowstorm.org/

Audubon suggests some tips to getting great owl shots in their Guide to Ethical Bird Photography.

Scott Weidensaul article: http://www.audubon.org/news/why-you-shouldnt-feed-or-bait-owls

Owl Research Institute: http://www.owlinstitute.org/

Blog: Great Gray Owls in Ottowa: Baiting and Abetting: A Great blog full of information concerning owls and baiting https://meadowhawk.wordpress.com/2013/02/19/great-gray-owls-in-ottawa-baiting-and-abetting/

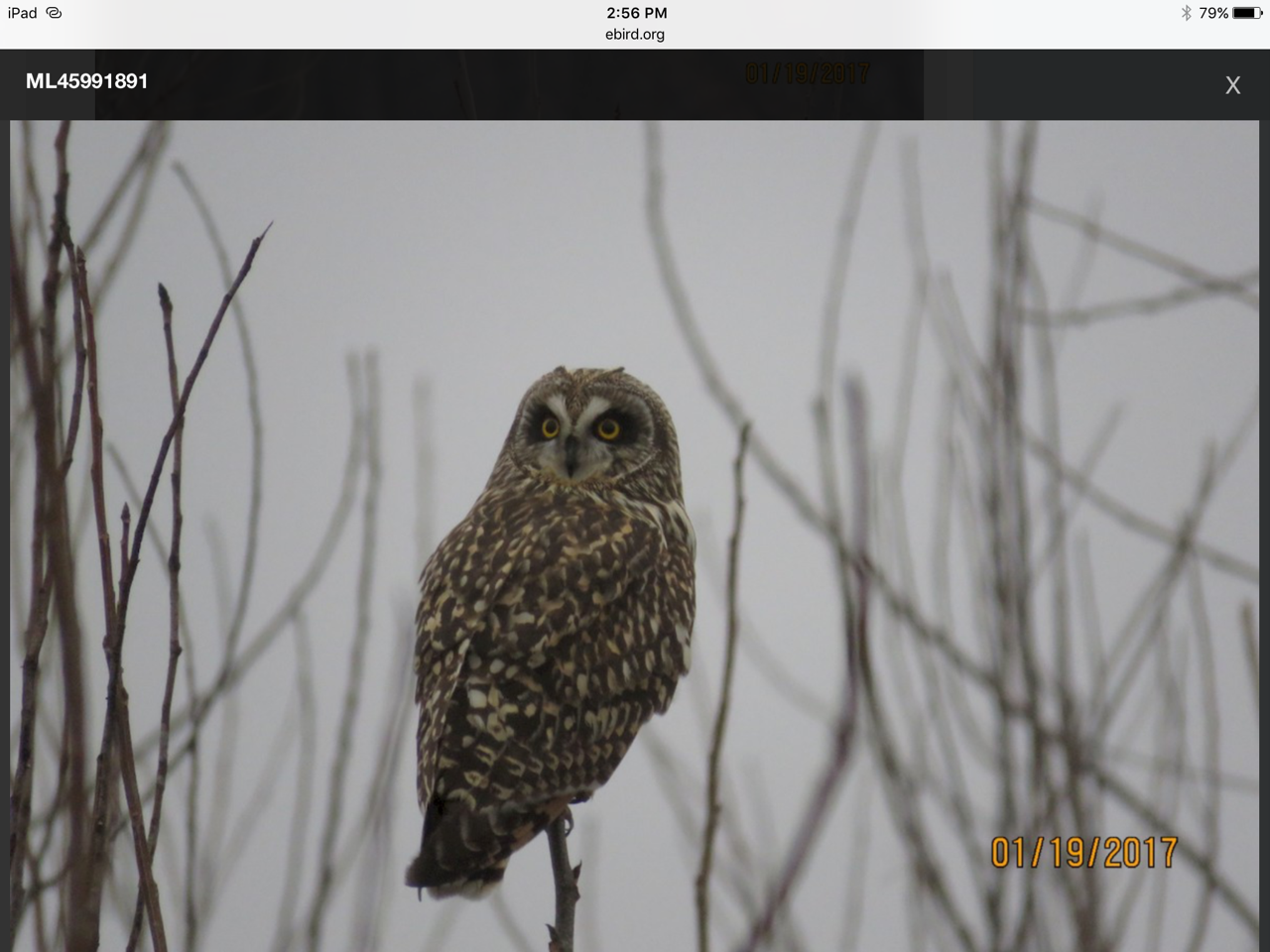

Gallery of Ethical Owl Images

With a lot of patience, and some luck, you could find yourself face-to-face with an owl like these photographers, without the use of playback or lures. Thanks to all who have contributed images!

Thoughts on Writing this Blog

I thought about if I could write anything positive about baiting owls. I wrote some words that made sense grammatically, and were certainly true. Then I deleted it. Writing a topic on baiting owls has been on my mind since 2016, when I was faced with the choice to go to Minnesota in winter to "clean up" on owls for my big year. I had heard of people baiting owls, and knew that some of the birds were in that area because food was easy. Not wanting my first look at a Northern Hawk Owl to be one waiting for a free handout, I decided not to go. I faced criticism from friends and birders who knew if I wanted to break 700 I needed to go see owls in winter. I managed to see and/or hear all owl species last year, avoiding using playback for most of them. I don't regret that choice, as I have the rest of my life to search out owls, as they reveal themselves to me.

Typos, factual errors, and mistakes/omissions are not intended, so if you spot something please contact thebirdingproject@gmail.com so it can be fixed. Thank you!